- Home

- Cyber stability

- Military Operations and AI: What Role for Humans in the Decision-Making Loop?

Military Operations and AI: What Role for Humans in the Decision-Making Loop?

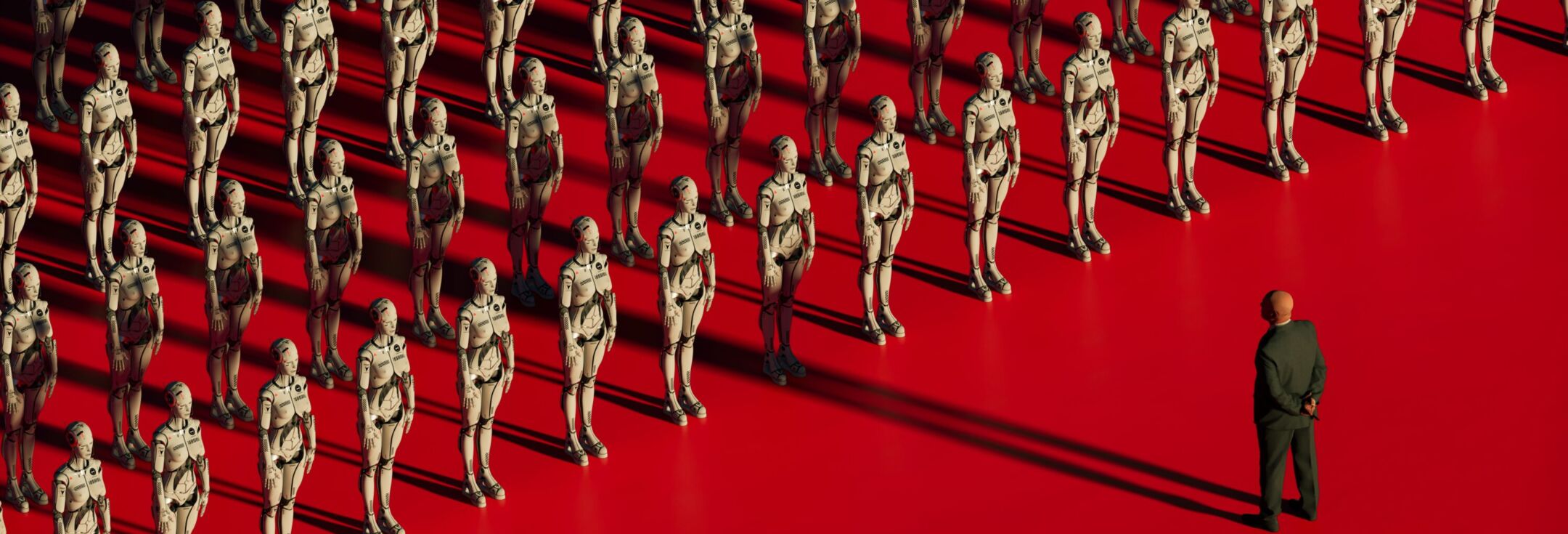

These questions were central to the roundtable discussion held at the InCYBER Forum in Lille, themed “Cyberdefense, Military Operations, and AI: What Role for Humans in the Decision-Making Loop?” By combining military, civilian, and ethical perspectives, the panelists painted a clear picture: AI is not replacing humans in decision-making but is fundamentally redefining their role.

A Decision-Making Loop That’s Faster, More Centralized… and Dehumanized?

“Our primary mission is to wage war, and our goal is to win it,” declared Colonel Patrice Tromparent, setting the tone for the debate. In achieving this mission, time is a crucial strategic lever. Too slow, and you’re overwhelmed. Too fast, and you make mistakes. The key is to “complete the loop faster than the adversary” — referring to the OODA loop: Observe, Orient, Decide, Act.

Artificial intelligence acts primarily as a speed multiplier: it shortens analysis time, suggests priorities, and proposes real-time options for handling objectives. “Where we needed 2,000 men in Afghanistan, we now only need 20,” explained Colonel Tromparent. In short, AI intervenes at every stage of the decision-making loop and heavily concentrates it. The American Maven program is a case in point: “Using heterogeneous data — satellite imagery, intercepts, situational maps — AI automatically proposes targets to humans. They validate them, and the AI transmits the targets to the most suitable weapons systems,” the colonel explained.

Here, AI doesn’t replace humans, but clearly reshapes their position in the decision process, centering it around an algorithmic core. Humans still “decide,” but within a framework that is pre-calibrated by the machine.

Western doctrines all affirm the necessity of keeping “humans in the loop.” But this principle remains vague. According to Éric Salobir, a human’s place in the decision-making loop is not binary but depends on multiple factors: the type of mission, the operational context, the nature of the decision (technical, operational, lethal), and the level of responsibility involved. David Byrne from the European Defence Agency described three coexisting configurations:

- In the loop: Humans decide, machines assist.

- On the loop: Humans supervise, intervening only if needed.

- Out of the loop: Machines act autonomously.

But even in the “in the loop” configuration promoted by Western nations, the algorithm’s influence on decision-making is significant: “If the machine says one solution has a 90% success rate and another only 10%, what military commander would choose the 10%?” questioned Colonel Tromparent. The main danger is not that AI takes over. The bigger risk — more subtle — is that humans step back out of habit or blind trust.

Human Responsibility Weakened by Technical Complexity

This shift directly affects the question of accountability. In AI-assisted operations, decision-making chains involve multiple actors and layers of analysis: data acquisition systems, databases, user interfaces, prioritization algorithms, tactical visualization tools. When an error occurs — such as striking the wrong target, misjudging a situation, miscalibrating an action, or causing collateral damage — who is to blame? The operator, the developer, the command? In any case, “Responsibility must remain human,” emphasized Éric Salobir. “No machine will ever be summoned before a war tribunal.”

During the debate, three key vulnerabilities in the military use of AI emerged:

- Structural bias: Military AIs are never neutral — they learn from past data in specific environments. “Data sets may not reflect new battlefield realities, especially in urban or asymmetric warfare,” Salobir warned. This exposes models to generalization errors, which are particularly risky in shifting contexts or against unconventional opponents.

- Black box effect: The more advanced a model (especially in deep learning), the less interpretable it becomes. In military settings, this lack of transparency poses a major problem: if we cannot explain why a target was selected, how can we justify striking it — legally or diplomatically?

- Susceptibility to deception: AI systems can be deliberately fooled. So-called adversarial attacks — where small, imperceptible changes are made to input data — can cause major classification errors. A visual artifact might make an armored vehicle appear as a civilian truck, or conceal a combatant’s presence.

Doctrine: The Strategic Tipping Point

Panelists agreed that most Western armed forces enforce strict safeguards: mandatory human oversight, compliance with international humanitarian law, decision traceability, and a ban on lethal strikes without human validation. This rigor is seen as a political choice, an ethical necessity, and a condition for societal acceptance. Colonel Tromparent emphasized, “We’re not trying to stoop to the level of a lawless adversary. There are other ways to win.”

However, this rigor can become a handicap if the adversary operates without such constraints. Some states or non-state actors already deploy autonomous systems without explicit human involvement — kamikaze drones, automated swarms, cognitive or cyber attacks. “Naturally, we’d rather send machines than soldiers, especially against an enemy who’s willing to use them,” noted Colonel Tromparent. Henri Schricke recalled the submarine warfare debate: too much restraint can cost the war. Hence the need to understand adversary tactics — even the darkest — to avoid being caught off guard. It’s not about abandoning one’s principles, but about not leaving innovation solely in the hands of those who ignore the rules.

As AI becomes entrenched in military operations, a delicate equation emerges between speed and judgment, effectiveness and accountability, automation and human control. Humans must “remain at the center of decision-making” — not as mere moral rubber stamps, but as informed, trained actors capable of assuming responsibility and understanding system limitations.

“The real asymmetry is not in technology. It’s in doctrine.” Henri Schricke’s statement sums up one of the central issues in AI’s military integration: what sets powers apart is not what they can do with AI, but what they allow themselves to do.

the newsletter

the newsletter