- Home

- Digital transformation

- Technology, geopolitics and the environment: the delicate equation of rare earths

Technology, geopolitics and the environment: the delicate equation of rare earths

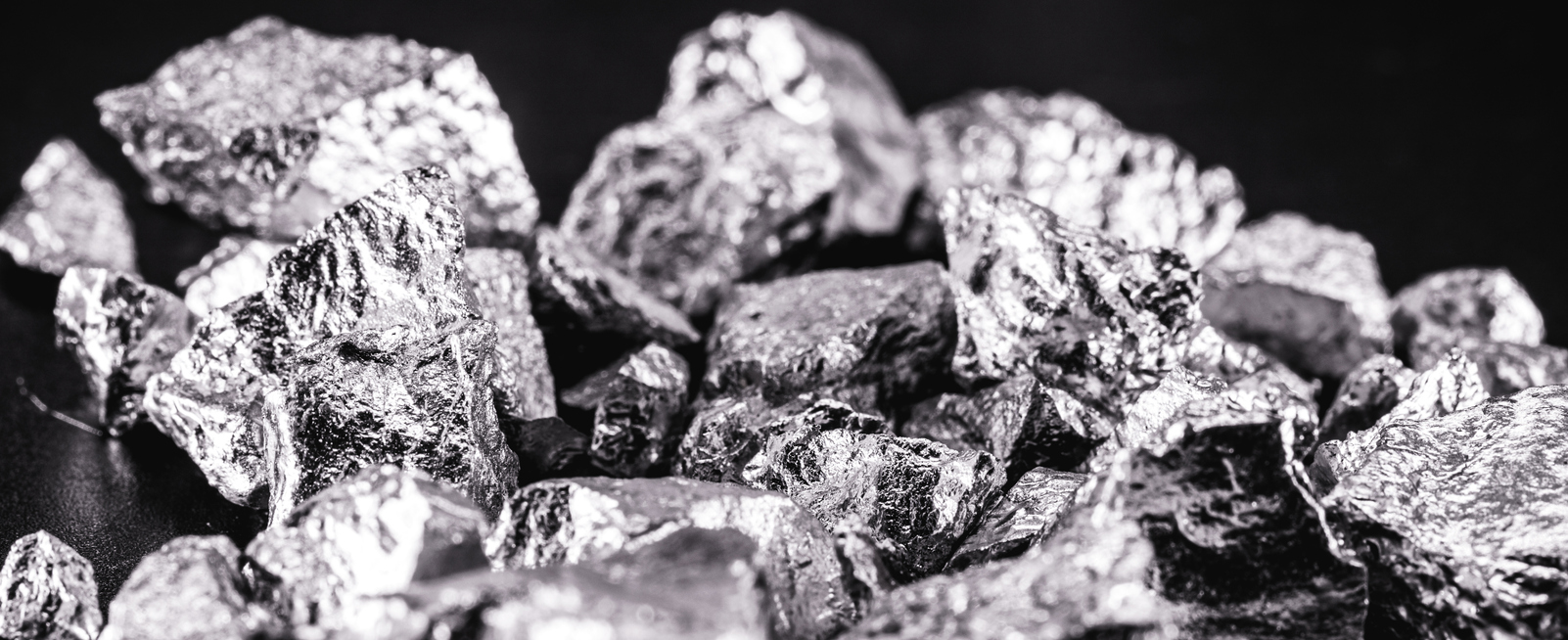

Portable telephones, hard drives, screens, electric vehicles, wind turbines, robots, 5G: rare earths are strategic primary resources essential to both technological progress and the environmental transition. Paradoxically, however, their extraction – over which China has a near monopoly – is highly polluting.

Rare earths, a group of 17 minerals with specific, electromagnetic properties, play an essential role in a wide range of technologies, including smartphones, wind turbines and rechargeable batteries. These strategic materials are at the heart of innovation, crucial to a number of electronic systems and needed to manufacture the powerful magnets used in electric engines.

Global demand for rare earths has seen exponential growth driven by the rapid expansion of the digital economy. The paradox of this resource lies in the fact that the elements required for green technology themselves contribute to harming the environment while they are extracted and refined. To date, no effective alternative has been found.

Despite their name, these resources are not intrinsically « rare »; some are present in abundance in the earth’s crust. Their rarity, however, lies in the complex process to extract and refine them. First, these elements can generally be found in ores in extremely low concentrations, making the extraction process costly and technically complex. For example, obtaining a kilo of lutetium requires fragmenting on average 1,200 tons of rock.

Secondly, the close chemical similarities between the various rare earth elements makes them difficult to separate, requiring sophisticated technologies and polluting chemicals.

Finally, their thorium or radioactive uranium content adds another layer of concern for the environment. According to Géo magazine, in China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, radioactivity levels measured in villages near the Baotou mine are 32 times higher than what is considered normal, even exceeding the figures observed at Chernobyl, which were 14 times normal. The same reason led to the relocation of the La Rochelle rare earths refinery – which accounted for 50% of the world market in the 1980s – to China.

Chinese monopoly and technological warfare

Until the 1980s, the United States dominated the rare earths market. China upended this trend with cheaper labor, larger deposits and less stringent environmental regulations. Since 1995, China has become the world’s leading producer, with a near monopoly on the extraction and refining of rare earths. According to the US Geological Survey, it has the world’s largest reserves at 44 million tons, representing over a third of those that have been identified (37%). With around 60% of the world extraction market and an even higher share in refining – up to 90% – dependence on China for these resources is a growing source of concern. The European Commission has reported that 98% of rare earths used in the EU are imported from China.

Faced with this growing dependency, the West has been looking for new sources. Since the late 2010s, mining and refining projects have sprung up in Australia and Canada. In 2013, the United States reopened the Mountain Pass open pit mine in California, which had been closed in 1998 after an accidental spill of thousands of liters of radioactive water. Rare earths have also become a major issue in the technological and trade war between the United States and China.

In June 2023, the Netherlands, under pressure from the USA, restricted the export of key technologies involved in microchip manufacturing. In response, on July 3, China’s Ministry of Commerce and Customs Administration declared that, as of August 1, exports of gallium and germanium – two rare earths of strategic importance for electronic chips – would require an export visa, a measure taken to « protect national security and interests ».

The EU looks for resilience

The Critical Raw Material Act published on March 16, 2023 demonstrated the European Union’s goal to bolster its resilience in rare earths. This act set ambitious targets to increase the European Union’s contributions to these substances, with 10% for extraction, 40% for processing and 15% for recycling. The proposal also recommends a fast, simplified permit procedure specifically for strategic extraction projects, to be handled by a national single point of contact.

The regulation suggests measures to diversify imports of crucial raw materials so that no more than 65% of each strategic raw material comes from a single third country, an effort to avoid too great a dependency on China.

What are the solutions?

In January 2023, Swedish group LKAB announced it had discovered a deposit of more than 1 million tons, representing 1% of the world’s identified reserves. LKAB will have to overcome considerable challenges, however, to get society to accept its exploitation. The comparable Nora Kärr deposit, also in Sweden, remained frozen for environmental reasons from 2017 to 2020, and although studies have resumed, the question of whether to exploit it remains unresolved. In any case, exploitation cannot begin before ten to fifteen years, the time needed to open a mine and bring it into service.

In terms of recycling, only 1% of rare earths are currently recycled, given their presence in small quantities rendering them difficult to separate from other metals. Reaching the ambitious 15% target faces many obstacles, ranging from long product lifetimes to complex collection processes, not to mention the breakneck pace of growth in the market for rare earths and the technologies that require them.

the newsletter

the newsletter