- Home

- Cyber stability

- Will the Moon soon get Internet?

Will the Moon soon get Internet?

The new wave of lunar exploration programs that began with the Artemis 1 mission last year will be very different than the program of the 1960s. The missions that will take off in the coming years will use telecommunications satellites deployed in a lunar orbit.

The second wave of lunar exploration that began with the Artemis program bears little technical resemblance to the pioneers of Apollo. Back then, the only assistance available for a smooth lunar landing was the photos taken by the first automated probes, such as NASA’s five lunar obiters that took pictures between 1966 and 1968. However, it was the Soviet Luna 9 that made the first soft-landing on the Moon on February 3, 1966, followed by the American Surveyor 1 on June 2.

For two years, the lunar orbiters mapped the surface to make way for the historic Apollo 11 mission with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin in July 1969. With no help other than the initial photographic reconnaissance, the LM Eagle’s on-board instruments and Armstrong’s piloting skills, the two astronauts landed seven kilometers from the planned landing site. Four months later on board Apollo 12, Pete Conrad and Alan Bean fared even better, landing precisely 163 meters from their target, the Surveyor 3 probe, which had been waiting in Oceanus Procellarum since April 20, 1967. However, this case was a one-off.

Marking the terrain

In the 1960s, the aim was to make good on President Kennedy’s lunar ambitions in less than ten years. In the 2020s, the goal is to make exploration of the Moon sustainable. Landing remains a challenging task, however. In 2023, the Japanese Hakuto-R and Russian Luna 25 probes failed to land. Bringing humans back to the lunar surface is planned for late 2025 with the Artemis 3 mission, but this also requires « marking the terrain« .

According to a study by consulting firm NSR, 400 lunar missions, including both institutional and private missions, are planned in the next few years. According to our information, these 400 missions (manned and automated) represent a market of « around 140 billion dollars » over the next ten years.

With this in mind, NASA is working on LunaNet: a project based on a framework of mutually agreed standards, protocols and interface specifications to allow future networks to be interoperable. For its part, on May 20, 2021, the European Space Agency (ESA) announced a feasibility study for a proposed network to provide navigation services, dubbed MoonLight. It will pave the way for the first stage of an Internet on the Moon. Two consortia have been appointed.

The first consortium is led by English company SSTL with SES and Airbus as well as Kongsberg Satellite Services and British satellite navigation company GMV-NSL. The second is headed by Telespazio and includes Thales Alenia Space (TAS), Inmarsat, Hispasat, MDA, OHB Systems, Altec and Nanoracks Europe. Moonlight’s initial funding of 153 million euros was approved by the ESA’s Ministerial Council Meeting in Paris (CM22) on November 22 and 23, 2022. A second tranche is expected at the council meeting in 2025.

Currently, the ESA is awaiting proposals from manufacturers. The chosen consortium could be announced in early 2024. In 2020, Nokia received 14.1 million dollars (13.3 million euros) in funding to test an LTE/4G system on the lunar surface on board Intuitive Machines’ Nova-C lander. Take-off for the Moon’s South Pole is expected with Falcon 9 in January 2024.

Joint services

What would be the practical advantages of a network of lunar satellites dedicated to navigation and communications? « They would allow manned and robot-manned missions to land wherever they want, » says Fabrice Joly, from the Future Projects and Applications division at ESA. The moving robots that will soon be surveying our moon’s surface will be able to move more quickly.

A memo from the French National Association for Technological Research (ANRT) in September 2022 points out that a lunar constellation for communication and navigation offers two benefits. The first is that « many missions are limited by their payload volume, their ability to transfer data from the Moon, or by difficulties in communicating with Earth in real time. Many missions are already suffering and will continue to suffer from limited navigation precision when descending to the Moon« .

The second benefit lies in the fact that the Moonlight constellation will « allow spacefaring nations and companies with limited budgets to nevertheless shoot for the Moon ». Given the short distance to the Moon, mobile vehicles and other equipment could be operated from Earth in near real time. In the longer term, commercial services could be considered.

Furthermore, using a joint telecommunications and navigation service could make it easier to design future missions by freeing up space on platforms for more scientific instruments or other cargo. This could help reduce costs. « With Moonlight, each individual mission is lighter, with less hardware and fewer complex, costly systems. », says Fabrice Joly.

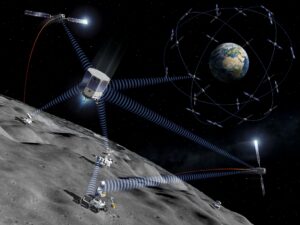

Moonlight will enable future missions to land anywhere on the Moon (ESA)

In time, a future customer

But what will the future network look like? Initially, the goal is to place into lunar orbit « three or four one-ton satellites, depending on how communication and navigation functions are distributed, » says Fabrice Joly. They could be positioned « above the four cardinal points of the Moon » to provide optimal services for future users, and not just ESA, which will eventually become a customer like any other.

Moonlight’s aim is to provide a service for all private and institutional missions. A subscription plan has been suggested to ensure the future system remains economically viable. However, the system needs to be tested first. In 2025, ESA plans to launch the Lunar Pathfinder demonstration satellite, developed by SSTL, into orbit around the Moon. Its payload will include an ESA GNSS receiver capable of detecting GNSS (Galileo/GPS) infrastructure signals. The experiment should demonstrate its future role in lunar navigation.

Developed by SSTL through SSTL Lunar, US company Firefly Aerospace is expected to launch it as part of NASA’s CLPS (Commercial Lunar Payload Service) initiative. Lunar Pathfinder will relay UHF and S-band telecommunications to the lunar surface and X-band telecoms to Earth.

Designed by SSTL, the Lunar Pathinder demonstrator is scheduled to launch around the Moon in 2025 (SSTL)

A head start for China

When it comes to lunar telecommunications relays, China is already one step ahead. In May 2018, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) deployed Queqiao-1, a small 425-kilogram satellite, to communicate with its Chang’E-4 lunar lander, which touched down on the Moon’s far side on January 3, 2019. In 2024, the Chang’E-6 probe, which is also aiming for the far side to bring rock samples back to Earth, will be equipped with the Queqiao-2 relay satellite.

In addition to Chang’E-6, Queqiao 2 should also serve as a relay for the future Chang’E-7 and Chang’E-8. China is only testing the foundations of its communications network for its own lunar station project, the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), which it officially announced in 2021. ILRS, which includes seven countries, including Russia, is a response to the Artemis program.

The long-term installation of lunar infrastructures will involve setting up a system to facilitate future arrivals from Earth. For Europe, this will mean strategic autonomy in communications and navigation for future missions, including the Argonaut supply ship. Moonlight should provide a landing accuracy of less than one hundred meters. This is crucial for the safe transport of new lunar explorers.

the newsletter

the newsletter